-

Addiction

-

Alcohol Abuse & Addiction

- Effects of Alcohol

- Casual Drinking

- High Functioning Alcoholic

- Alcohol Rehab

- Alcohol Detox

- Alcohol Recovery

Alcohol Abuse & Addiction -

Drug Addiction

-

Prescription Drug Addiction

-

Co-Occurring Disorders

-

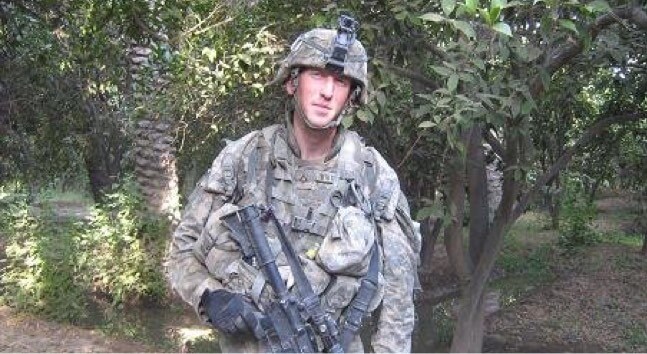

Who Addiction Affects

-

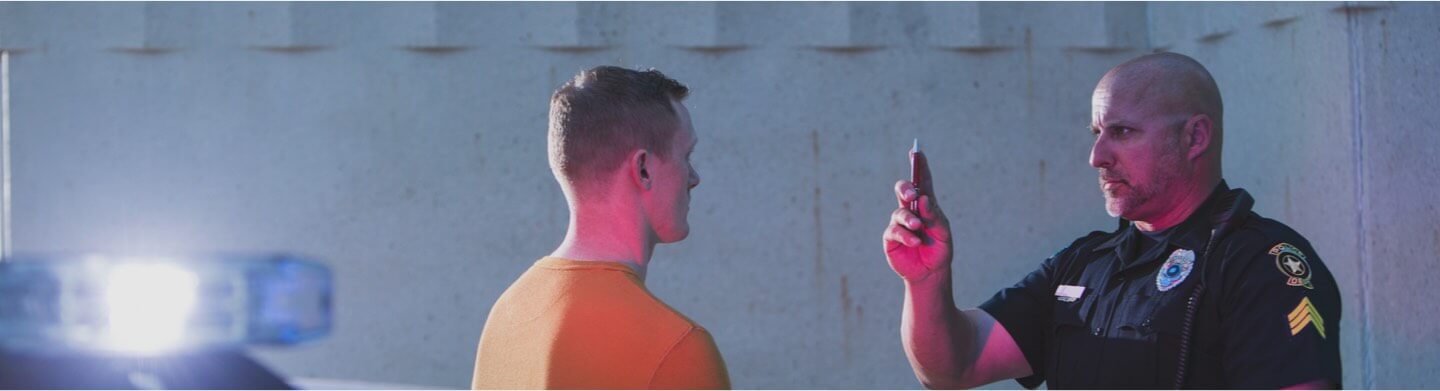

Signs and Symptoms

Addiction

Addiction

DrugRehab.com provides information regarding illicit and prescription drug addiction, the various populations at risk for the disease, current statistics and trends, and psychological disorders that often accompany addiction. You will also find information on spotting the signs and symptoms of substance use and hotlines for immediate assistance.

-

Alcohol Abuse & Addiction

-

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment for addiction takes many forms and depends on the needs of the individual. In accordance with the American Society of Addiction Medicine, we offer information on outcome-oriented treatment that adheres to an established continuum of care. In this section, you will find information and resources related to evidence-based treatment models, counseling and therapy and payment and insurance options.

-

Active Recovery

-

12-Step Programs

-

Faith & Religion

Faith & Religion

Faith & Religion

Treatment for addiction takes many forms and depends on the needs of the individual. In accordance with the American Society of Addiction Medicine, we offer information on outcome-oriented treatment that adheres to an established continuum of care. In this section, you will find information and resources related to evidence-based treatment models, counseling and therapy and payment and insurance options.

-

Sober Living Homes

-

Support for Family & Friends

-

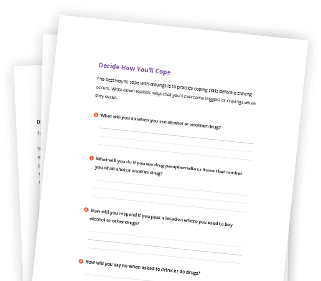

Relapse

Active Recovery

Active Recovery

The recovery process doesn't end after 90 days of treatment. The transition back to life outside of rehab is fraught with the potential for relapse. Aftercare resources such as 12-step groups, sober living homes and support for family and friends promote a life rich with rewarding relationships and meaning.

-

12-Step Programs

-

Find A Rehab Center

-

Georgia

- The Recovery Village Atlanta

Georgia -

New Jersey

- The Recovery Village Cherry Hill at Cooper

New Jersey -

Ohio

-

Colorado

-

Maryland

- IAFF Center of Excellence

Maryland -

Missouri

- The Recovery Village Kansas City

Missouri -

Florida

-

Washington

- The Recovery Village Ridgefield

Washington

Our Community

Our Community

Our community offers unique perspectives on lifelong recovery and substance use prevention, empowering others through stories of strength and courage. From people in active recovery to advocates who have lost loved ones to the devastating disease of addiction, our community understands the struggle and provides guidance born of personal experience.

-

Georgia